How Democratic Coarse-Graining Filters Against Some of the Research That Matters Most

This article is part of a series of articles I am releasing as part of a research project with the Wolfram Institute. This project is intending to answer the question: How can DeSci DAO's better align incentives for funding important science research? Two pieces of the project that I will be referencing in this article are a historical analysis I did of 5 different transformative technologies from 1950 to now. I will also be referencing a number of largely anonymous interviews I did with many experts in DeSci, science funding, and beyond, that I did to help answer this research question. This is the first of six articles I will be releasing for the project so look out for more soon!

The problem with funding what we can measure

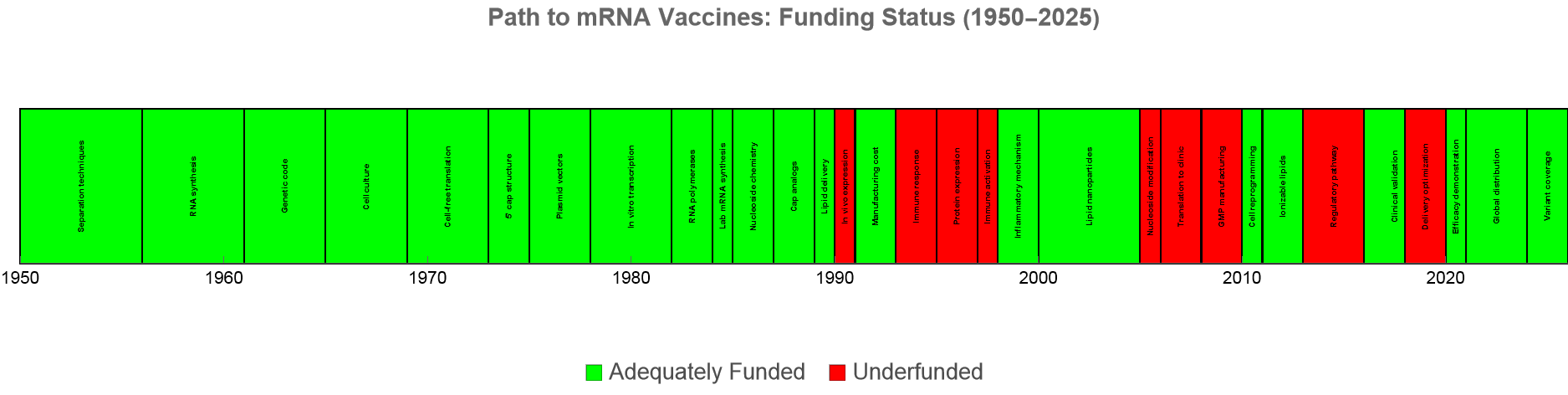

COVID-19 vaccines took eleven months from genetic sequence to first injections. Record time for a technology never before approved in humans. Less impressive compared to H1N1, a case where proven vaccine technology cut that timeline roughly in half. When you read that mRNA vaccines hadn't been approved before, you might assume the technology was a lucky break. A direction we had started research on just before COVID. Unfortunately, the opposite is true. mRNA vaccine development began in the late 1980s, but languished for decades due to lack of funding; in the 1990s and most of the 2000s, nearly every vaccine company that considered working on mRNA opted to invest its resources elsewhere. Katalin Karikó, who later won a Nobel Prize for this work, failed to secure grants for over a decade because "RNA was considered too hard to work with, too unstable, and the whole idea too full of fresh problems". Her persistence got her demoted four times at the University of Pennsylvania. Had public funders backed mRNA earlier, vaccines might have been deployment-ready when COVID arrived. Our response timeline could have looked much closer to H1N1's. A difference measured in millions of lives.

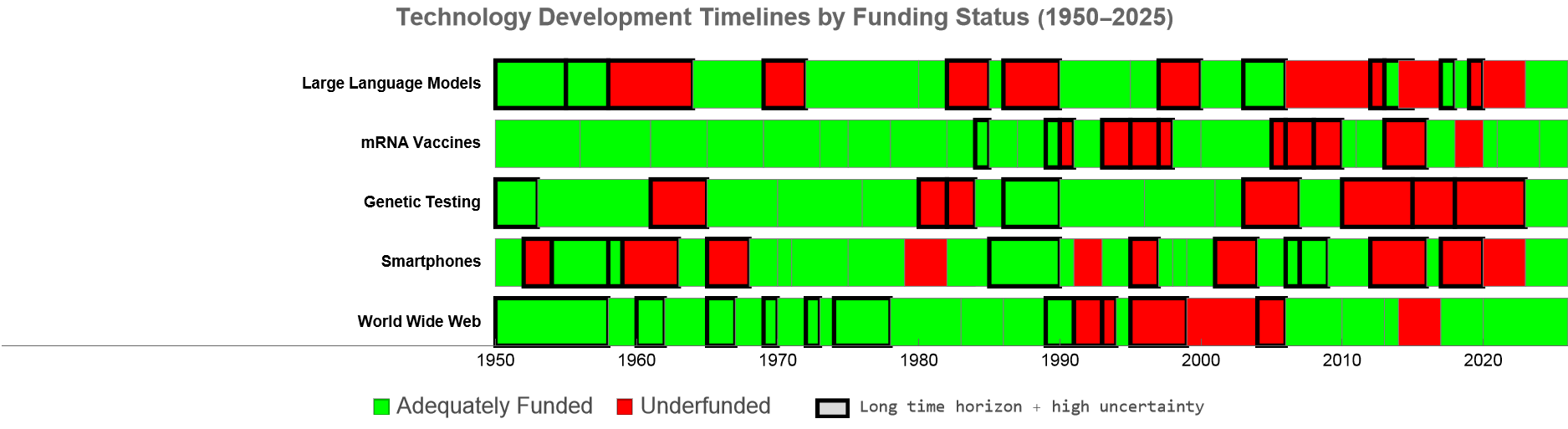

The mRNA story is, unfortunately, not an outlier. Research with longer time horizons and higher uncertainty faces systematically lower funding rates than incremental work with predictable outcomes. In a historical analysis where I went through 64 different sources to create a 75 year timeline on the research and development that ended up being required for five different transformative technologies: mRNA vaccines, genetic testing, large language models, smartphones/personal computing, and the world wide web. Research periods which had long time-horizons to results and high-uncertainty were about three times more likely to go through a tragic "underfunding" period similar to the mRNA example.

There are mechanisms which reinforce this bias at every stage of the public funding process. Major agencies require preliminary data, creating a catch-22 for novel research where gathering that data itself requires funding. Grant proposals must articulate clear milestones and deliverables, excluding exploratory work where outcomes cannot be predicted. Peer review systematically favors conservative proposals. Career metrics like publications bias against novel work, since breakthroughs often require longer publication gaps. Even programs designed for high-risk research don't encourage risk-taking for non-tenured scientists, and early-career researchers with novel track records are less likely to be funded, likely because they're still evaluated by the larger system's metrics. Each stage independently selects against high-risk, long-term research; together they systematically exclude a whole category of essential science.

These mechanisms emerge from one simple fact: public research funding in a democracy requires public justification. Agencies must defend their budgets to legislators who must defend their votes to constituents. This chain of accountability creates implicit pressure toward research programs that can demonstrate progress within politically relevant timeframes. The question is not whether individual program officers prefer short-term research, but whether the system can sustain funding for work whose payoffs lie beyond the next election.

The formalization of this phenomenon is well covered in Seeing Like a State by James C. Scott. Legibility is one of the main subjects: the need for large states to make things "administratively visible" for measurement and evaluation. Elected officials, legislative committees, and ultimately voters need to understand whether public investments are responsible uses of taxpayer funds. The epistemic complexity of research makes this a challenging problem for democratic stakeholders who lack specialized knowledge to evaluate the value of research. Because most oversight bodies cannot directly assess scientific merit, they must rely on proxy indicators that non-specialists can interpret.

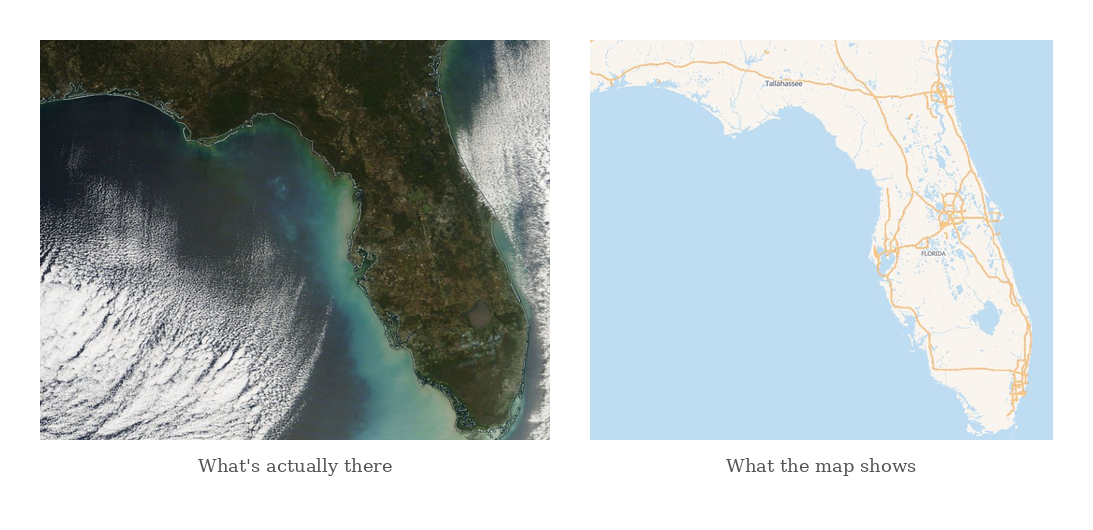

Stephen Wolfram's work on observers and coarse graining provides a useful framework for understanding legibility at a deeper level. In statistical mechanics, coarse graining describes how computationally bounded observers extract usable information from systems too complex to track in full detail. When observing a gas, we don't follow every molecule, we measure temperature and pressure. We conflate many possible microscopic configurations into aggregate properties we can actually work with.

Public funding agencies are computationally bounded observers of research. They cannot track the detailed trajectory of every investigation, cannot evaluate technical merit without proxy indicators, cannot predict which speculative directions will prove transformative. They must coarse grain. Legibility requirements are, in this framing, demands that research be amenable to coarse graining. Its significance must be communicable without engaging the full complexity of the work itself. The problem is that transformative research often resists coarse graining. The details matter. The value emerges from the specific path of investigation, not from properties visible at the aggregate level.

Florida, my home state, with a satellite image (credit: NASA Worldview) and street map view (credit: Shortbread/OpenStreetMap). The street map view is missing out on a lot of information because it is coarse-grained to be more legible to computationally bounded observers (that drives cars).

This framing explains why the problem is so persistent. In Wolfram's account, the interplay between complex underlying dynamics and the bounded nature of observers is what gives rise to the Second Law of Thermodynamics: entropy increases because observers cannot track the fine-grained details that would reveal underlying order. Similarly, the "entropy" of public research funding, its drift toward safe and incremental work, emerges from the mismatch between the fine-grained nature of transformative research and the coarse-graining requirements of democratic accountability. This outcome emerges from the structural relationship between what research is and what oversight can measure.

In the historical analysis and interviews several seemingly unrelated biases in public funding popped up. However, viewed through this lens these biases all receive one unifying explanation as different facets of the same coarse-graining requirement.

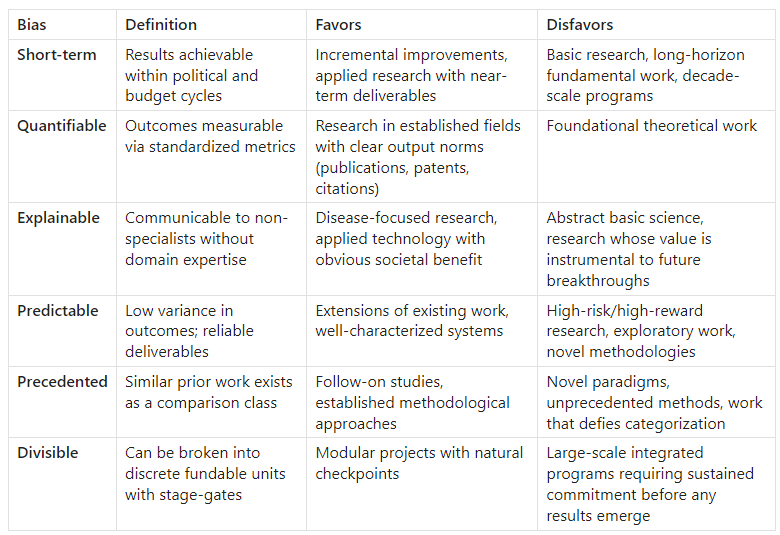

Six dimensions of coarse-graining bias in public funding.

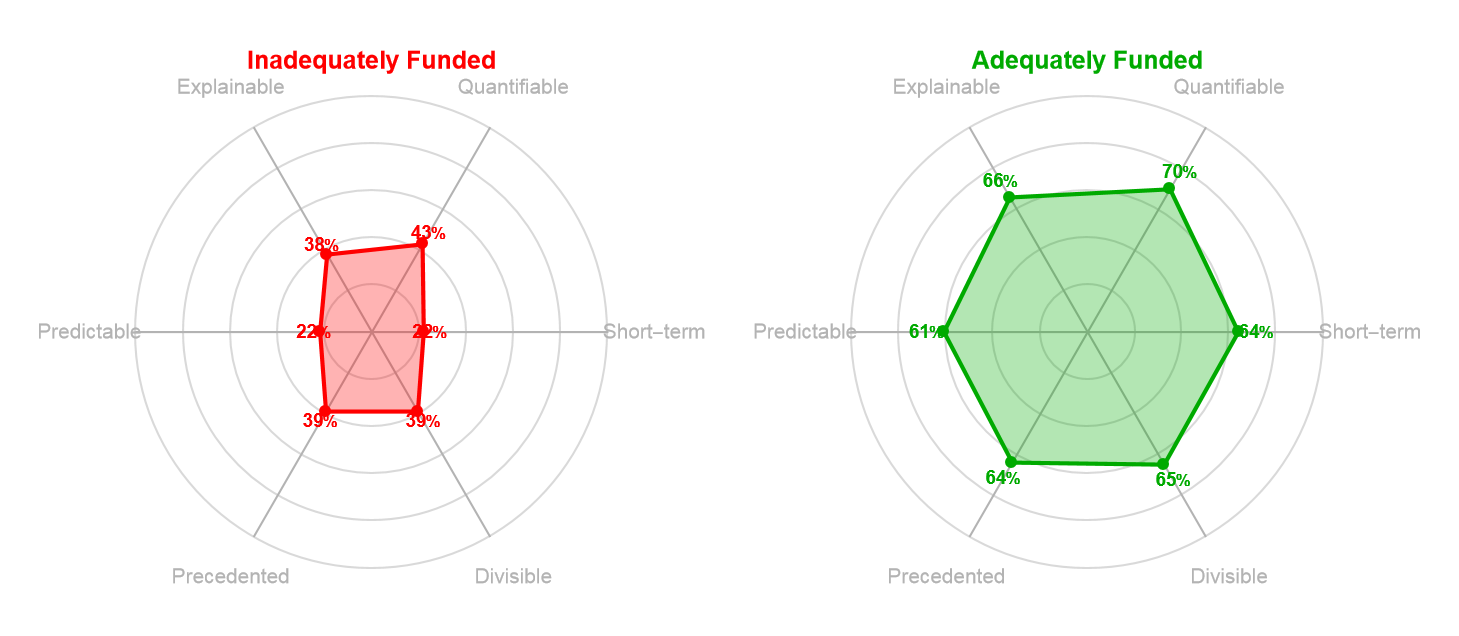

Each of these biases is a different way of asking whether research can be coarse grained. Short-term bias asks whether outcomes can be compressed into political timescales. Quantifiability asks whether progress can be reduced to standardized metrics. Explainability asks whether significance can be communicated without domain expertise. Predictability asks whether outcomes can be forecast from inputs. Precedent asks whether the research can be understood by analogy to prior work. Divisibility asks whether the program can be decomposed into independently evaluable stages. Research that scores well on these dimensions is coarse-grainable: its value can be assessed through aggregate indicators without engaging the full complexity of the work. Research that scores poorly resists coarse graining: one has to engage with the details to understand what they'll get.

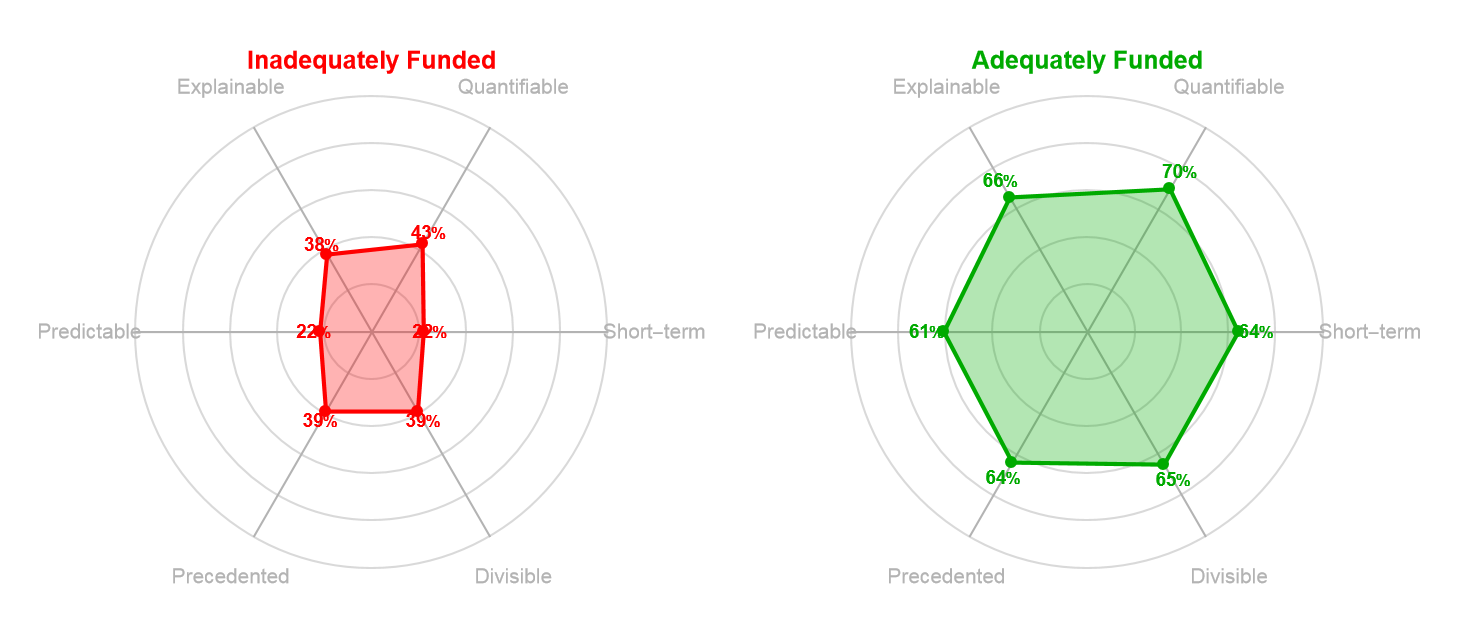

When we examine the historical funding patterns from before, this framework predicts outcomes with striking accuracy. Across the five technologies, the contrast between underfunded and funded periods was closely related to whether or not the research could be coarse grained along these dimensions. For example, the mRNA research discussed earlier resisted coarse graining on nearly every dimension. At that time Katalin Karikó's research impact was long-term, difficult to quantify before proof-of-concept, hard to explain without immunology training, highly unpredictable, with very little precedent for clinical applications. Its decades of underfunding was a predictable outcome of asking fine-grained research to meet coarse-graining requirements. When we look at how underfunded vs. funded research performs on these 6 parameters we get a better understanding of the effect noted earlier.

There are exceptions to these patterns. DARPA came up repeatedly in interviews as the most prominent exception to the standard patterns in public funding. However these exceptions prove the rule. DARPA's ability to fund long-term, high-risk, high-potential research happens precisely because its institutional design insulates it from typical democratic accountability pressures. Program managers serve fixed terms of three to five years, rotating in from academia and industry rather than building permanent bureaucratic careers dependent on sustained congressional approval. They report directly to the agency director, enabling rapid funding decisions without extended justification processes. Critically, DARPA's defense mandate provides political cover: national security arguments deflect the scrutiny that civilian research agencies face when funding speculative work. The agency can fund research that resists coarse graining because its accountability runs through defense priorities rather than democratic legibility requirements.

If one wanted to do a controlled experiment to falsify the idea that insulation from coarse-graining demands is truly the operative variable working in DARPA's success, then they might try to replicate DARPA's organizational structure without its protection from legibility pressures. The creators of ARPA-E inadvertently performed this exact experiment. Established in 2009 to apply the DARPA model to energy research, ARPA-E adopted similar features: autonomous program managers, milestone-based funding, and an explicit transformative mandate. Yet without the bipartisan defense consensus and classification barriers that shield DARPA from scrutiny, ARPA-E became entangled in partisan energy and climate debates. Its budget has faced recurring elimination proposals from presidential administrations and sharp cuts from Congress. This political exposure has pushed the agency toward safer, more coarse-grainable investments, precisely the pattern the DARPA model was designed to escape.

The DARPA example suggests a path forward, but replicating their political insulation is not scalable. Not every research domain can shelter under defense mandates or supranational governance. Yet the deeper lesson is that different selection mechanisms have different blind spots, and valuable research slips through wherever those blind spots overlap. DARPA funded the early internet and GPS when conventional agencies saw no clear application. These were not lucky accidents. They were the predictable result of applying different evaluation criteria to the same pool of potential research. Viewed this way, the value of funding diversity should hardly be surprising.

Allocating research funding is fundamentally an exercise in forecasting under uncertainty. At its core, every grant decision implicitly answers the question: which investigations will yield societally transformative knowledge? This reframing matters because it shifts the question from "which funding mechanism is best?" to "how do we optimize predictions across an inherently unpredictable landscape?" The answer, as forecasting research increasingly demonstrates, lies not in finding the perfect oracle but in aggregating diverse perspectives. Philip Tetlock's empirical work on prediction is some of the seminal work here. Diverse teams of forecasters consistently outperform homogeneous expert panels, even when individual experts possess superior domain knowledge. When forecasters use genuinely different models and information sources, their errors become uncorrelated, and aggregation yields substantial accuracy gains. If science funding is a prediction problem then the implication is clear. A portfolio of funding sources with genuinely different selection criteria should identify a broader range of ultimately valuable research than any single mechanism could achieve alone.

Unfortunately, the current landscape reveals remarkable homogeneity. Of the approximately $2.8-3.1 trillion spent annually on R&D worldwide, 70-75% is spent based on decisions made internally by corporations. Among mechanisms explicitly oriented toward human welfare, the concentration is starker: government peer review and mission-directed allocation control over 90% of public R&D. Alternative mechanisms, such as prizes, philanthropy, and DARPA-style discretion, collectively represent less than 3%. A few selection philosophies, all constrained by the coarse-graining requirements outlined above, determine the trajectory of publicly-funded science globally.

How do we create many more science funding mechanisms as quickly as possible? Decentralized Science (DeSci) DAOs offer one compelling path forward. These are research funding organizations built on web3 technology that operate in largely unregulated space. Unlike charities, foundations, or companies, which require fixed governance structures and extensive legal compliance, DAOs can be spun up quickly and their organizational rules can be programmed and modified at will. This includes how funding decisions get made, how contributors are incentivized, what timelines projects operate on, what counts as success. Organizations like ResearchHub, VitaDAO, and Molecule already operate outside the traditional structures that push other science funders toward the same few funding methodologies.

In interviews, people deeply involved in DeSci DAOs all repeatedly emphasized the same point: a significant value add of these organizations is in their role as an experimental testbed for science funding itself. The barrier to creating a new DAO is relatively low, and their rules can be rewritten easily. Because of this, they can be used to run many parallel experiments on how to fund research. A funding mechanism that fails generates valuable information about incentive design. A mechanism that succeeds demonstrates viability for approaches public funders cannot politically sustain. We do not yet know which alternative funding structures will best identify the fine-grained research that current mechanisms miss. However, we have better tools to run the experiments and find out than ever before.