Institute Output

On the Concept of Motion

Stephen Wolfram

It seems like the kind of question that might have been hotly debated by ancient philosophers, but would have been settled long ago: how is it that things can move? And indeed with the view of physical space that’s been almost universally adopted for the past two thousand years it’s basically a non-question. As crystallized by the likes of Euclid it’s been assumed that space is ultimately just a kind of “geometrical background” into which any physical thing can be put—and then moved around.

The Physicalization of Metamathematics and Its Implications for the Foundations of Mathematics

Stephen Wolfram

One of the many surprising (and to me, unexpected) implications of our Physics Project is its suggestion of a very deep correspondence between the foundations of physics and mathematics. We might have imagined that physics would have certain laws, and mathematics would have certain theories, and that while they might be historically related, there wouldn’t be any fundamental formal correspondence between them.

But what our Physics Project suggests is that underneath everything we physically experience there is a single very general abstract structure—that we call the ruliad—and that our physical laws arise in an inexorable way from the particular samples we take of this structure.

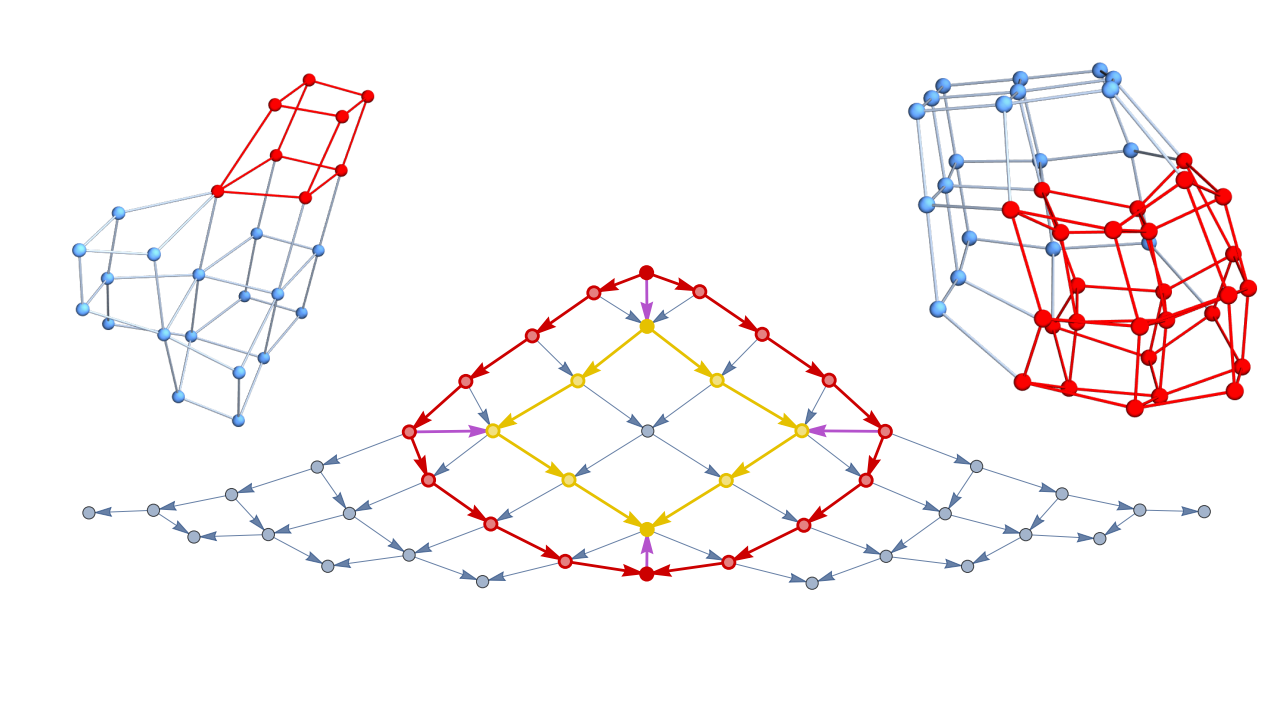

Homotopies in Multiway (Non-Deterministic) Rewriting Systems as n-Fold Categories

Xerxes D. Arsiwalla, Jonathan Gorard, Hatem Elshatlawy

Pregeometric Spaces from Wolfram Model Rewriting Systems as Homotopy Types

Xerxes D. Arsiwalla, Jonathan Gorard

The study explores how spatial structures in physics can emerge from pregeometric combinatorial models governed by computational rules, using higher category theory and homotopy types.

The Concept of the Ruliad

Stephen Wolfram

I call it the ruliad. Think of it as the entangled limit of everything that is computationally possible: the result of following all possible computational rules in all possible ways. It’s yet another surprising construct that’s arisen from our Physics Project. And it’s one that I think has extremely deep implications—both in science and beyond.

Some Relativistic and Gravitational Properties of the Wolfram Model

Jonathan Gorard

The article shows that causal invariance in the Wolfram Model leads to discrete general and Lorentz covariance, introducing curvature concepts for hypergraphs related to the Ricci tensor and Einstein field equations

Algorithmic Causal Sets and the Wolfram Model

Jonathan Gorard

This study links causal set theory and the Wolfram model, showing hypergraph rewriting facilitates causal set evolution, infers conformal invariance, and derives the Benincasa-Dowker action from discrete Einstein-Hilbert action.

Hypergraph Discretization of the Cauchy Problem in General Relativity via Wolfram Model Evolution

Jonathan Gorard

This article introduces a numerical general relativity code using the Z4 formulation with hypergraph-based Cauchy data and adaptive mesh refinement, validating results against standard spacetimes and comparing with Wolfram model evolution.

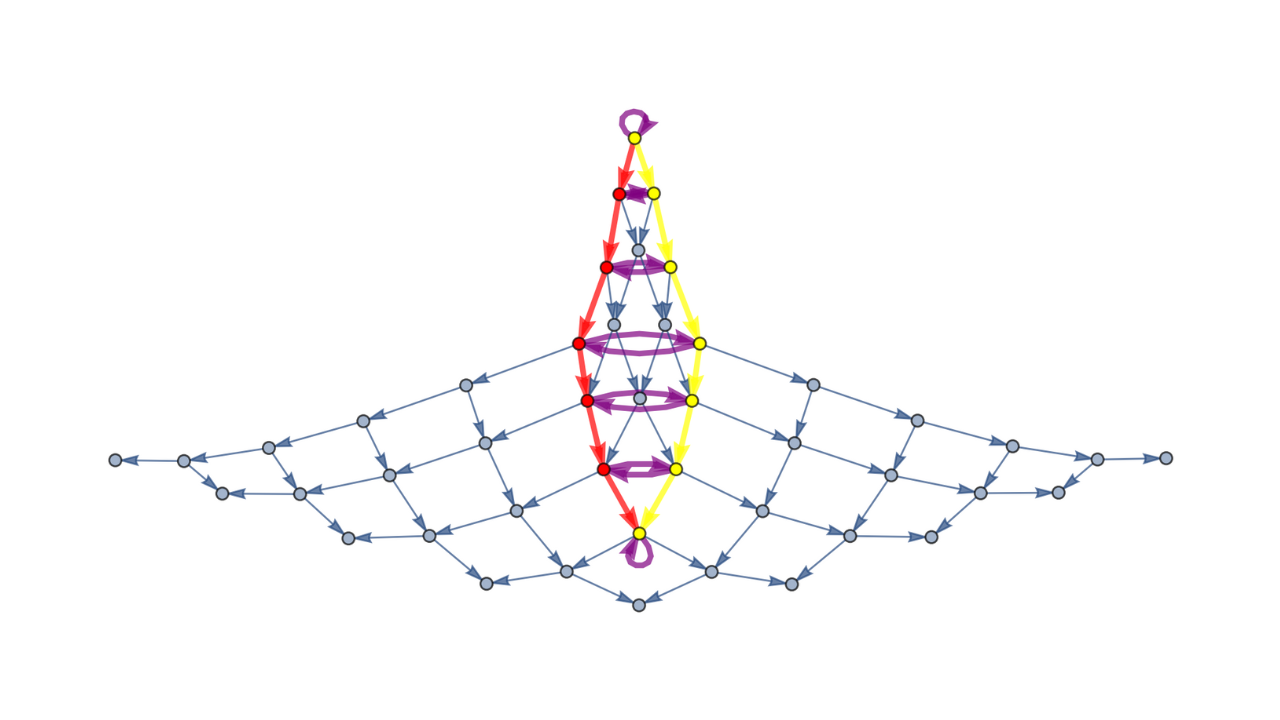

Multicomputation with Numbers: The Case of Simple Multiway Systems

Stephen Wolfram

Multicomputation is an important new paradigm, but one that can be quite difficult to understand. Here my goal is to discuss a minimal example: multiway systems based on numbers. Many general multicomputational phenomena will show up here in simple forms (though others will not). And the involvement of numbers will often allow us to make immediate use of traditional mathematical methods.

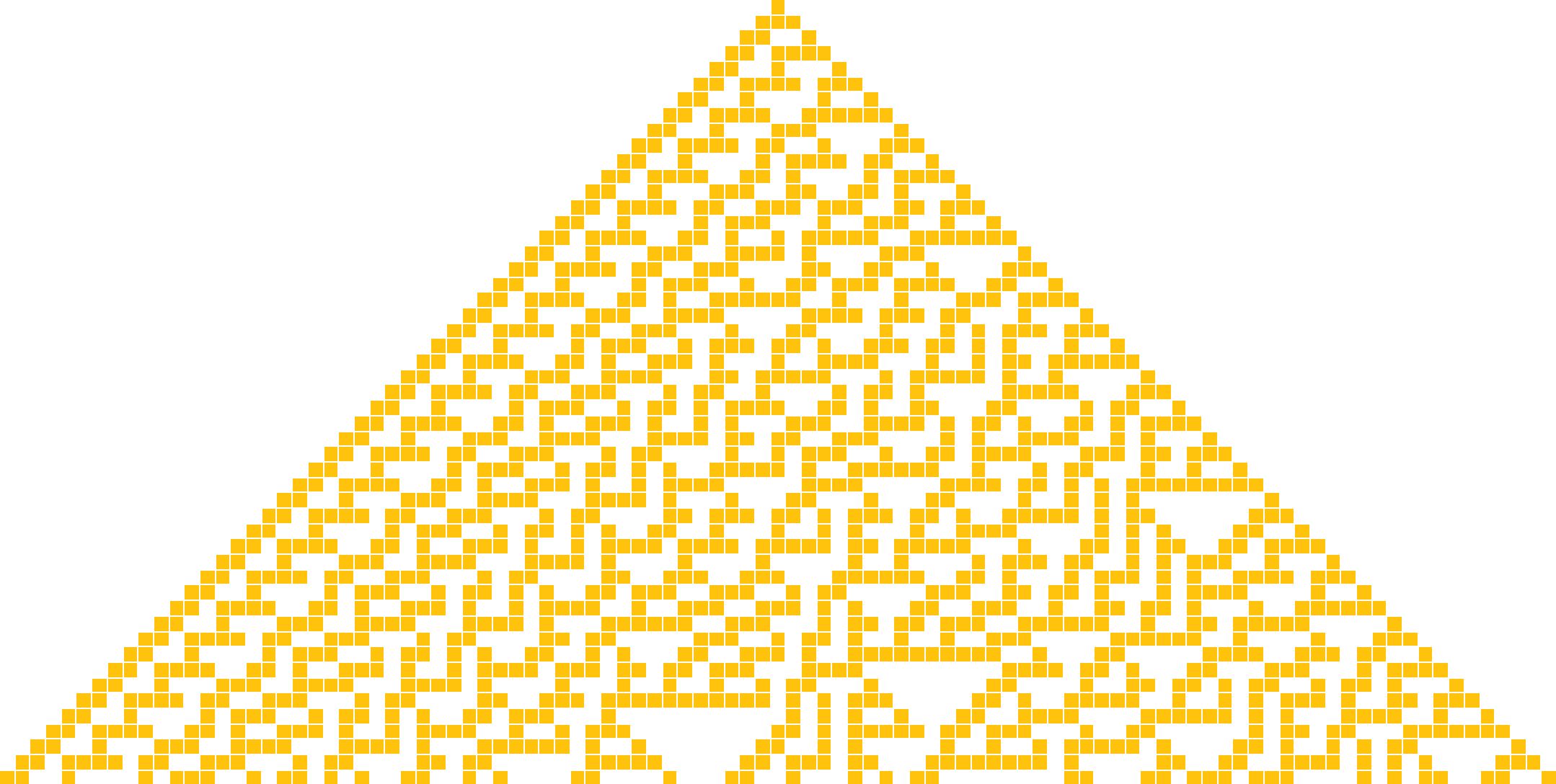

Charting a Course for “Complexity”: Metamodeling, Ruliology and More

Stephen Wolfram

For me the story began nearly 50 years ago—with what I saw as a great and fundamental mystery of science. We see all sorts of complexity in nature and elsewhere. But where does it come from? How is it made? There are so many examples. Snowflakes. Galaxies. Lifeforms. Turbulence. Do they all work differently? Or is there some common underlying cause? Some essential “phenomenon of complexity”?

Multicomputation: A Fourth Paradigm for Theoretical Science

Stephen Wolfram

One might have thought it was already exciting enough for our Physics Project to be showing a path to a fundamental theory of physics and a fundamental description of how our physical universe works. But what I’ve increasingly been realizing is that actually it’s showing us something even bigger and deeper: a whole fundamentally new paradigm for making models and in general for doing theoretical science. And I fully expect that this new paradigm will give us ways to address a remarkable range of longstanding central problems in all sorts of areas of science—as well as suggesting whole new areas and new directions to pursue.

How Inevitable Is the Concept of Numbers?

Stephen Wolfram

The aliens arrive in a starship. Surely, one might think, to have all that technology they must have the idea of numbers. Or maybe one finds an uncontacted tribe deep in the jungle. Surely they too must have the idea of numbers. To us numbers seem so natural—and “obvious”—that it’s hard to imagine everyone wouldn’t have them. But if one digs a little deeper, it’s not so clear.

The Problem of Distributed Consensus

Stephen Wolfram

In any decentralized system with computers, people, databases, measuring devices or anything else one can end up with different values or results at different “nodes”. But for all sorts of reasons one often wants to agree on a single “consensus” value, that one can for example use to “make a decision and go on to the next step”.

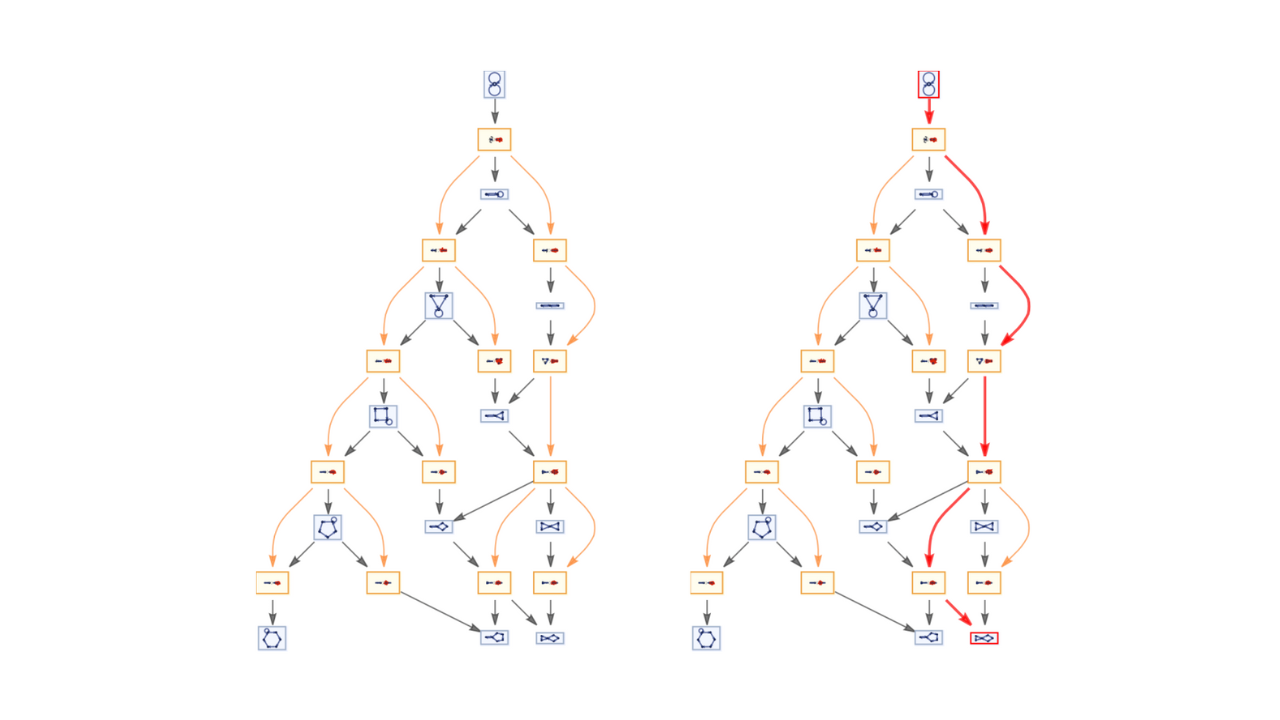

Fast Automated Reasoning over String Diagrams using Multiway Causal Structure

Jonathan Gorard, Manojna Namuduri, Xerxes D. Arsiwalla

Why Does the Universe Exist? Some Perspectives from Our Physics Project

Stephen Wolfram

Why does the universe exist? Why is there something rather than nothing? These are old and fundamental questions that one might think would be firmly outside the realm of science. But to my surprise I’ve recently realized that our Physics Project may shed light on them, and perhaps even show us the way to answers.

The Wolfram Physics Project: A One-Year Update

Stephen Wolfram

When we launched the Wolfram Physics Project a year ago today, I was fairly certain that—to my great surprise—we’d finally found a path to a truly fundamental theory of physics, and it was beautiful. A year later it’s looking even better. We’ve been steadily understanding more and more about the structure and implications of our models—and they continue to fit beautifully with what we already know about physics, particularly connecting with some of the most elegant existing approaches, strengthening and extending them, and involving the communities that have developed them.

ZX-Calculus and Extended Wolfram Model Systems II: Fast Diagrammatic Reasoning with an Application to Quantum Circuit Simplification

Jonathan Gorard, Manojna Namuduri, Xerxes D. Arsiwalla

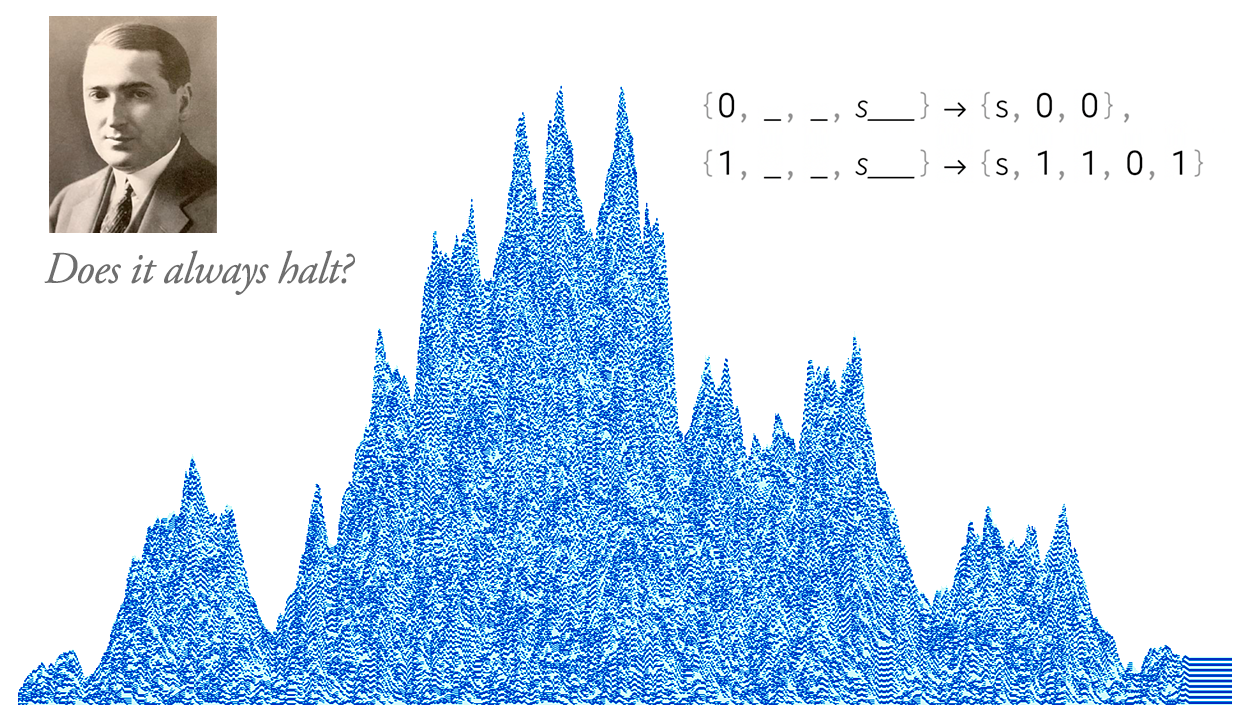

A Little Closer to Finding What Became of Moses Schönfinkel, Inventor of Combinators

Stephen Wolfram

For most big ideas in recorded intellectual history one can answer the question: “What became of the person who originated it?” But late last year I tried to answer that for Moses Schönfinkel, who sowed a seed for what’s probably the single biggest idea of the past century: abstract computation and its universality.

What Is Consciousness? Some New Perspectives from Our Physics Project

Stephen Wolfram

Consciousness is a topic that’s been discussed and debated for centuries. But the surprise to me is that with what we’ve learned from exploring the computational universe and especially from our recent Physics Project it seems there may be new perspectives to be had, which most significantly seem to have the potential to connect questions about consciousness to concrete, formal scientific ideas.

After 100 Years, Can We Finally Crack Post’s Problem of Tag? A Story of Computational Irreducibility, and More

Stephen Wolfram

For Post, the failure to crack his system derailed his whole intellectual worldview. For me now, the failure to crack Post’s system in a sense just bolsters my worldview—providing yet more indication of the strength and ubiquity of computational irreducibility and the Principle of Computational Equivalence.